Speech at the Cosmos Club in December 2019 — Institute of Current World Affairs, Washington, DC

Historic xenophobia in France in the context of current anti-immigrant sentiments

[You can watch the video of this speech and the dramatic negative reaction of the French First Secretary of the Embassy at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lZxVHg2rz3M]

I like to claim that I am the descendant of a poor refugee from North Africa… it is a bit of a stretch of course as that refugee arrived more than 200 years ago. My mother’s maiden name is Gadala. The great-great-great grandfather of my mother — Theodore Gadala born in Farshut in Upper Egypt — arrived at 16 years old with a group of a few hundred men, women, and children in Marseille in October 1801 after sailing on English boats with the French army as it retreated from Egypt. A soldier in the Coptic legion of Bonaparte’s army, he later described himself as a “Mameluke of the Imperial Guard”. The young Theodore was part of men who had thrown in their lot with Bonaparte’s army in Egypt and who feared local retaliation once it withdrew. The group included many Christians of Coptic Orthodox, Greek Orthodox and Armenian background; they also included Muslims, some mamluks, or military slaves, who had been born in places like Georgia where the Ottoman Empire extracted recruits. Not many were really Egyptians, but their common language was Arabic. Like many refugees — even nowadays — they thought it was temporary — a few months at most — that soon the French would win Egypt again against the Turks or the British and they would return home. General Ya’qub, their Coptic leader had drawn up a plan to reinvade and liberate Egypt from Turkish domination, but he tragically died during the trip to Marseille putting an abrupt end to the plan and collapsing their political hopes. No longer political exiles, they now faced permanent resettlement in France.

Before I tell you more about the fate of Theodore and his companions, I will reiterate that my intent is not to make a simplistic rebuke to a complex issue by telling a family anecdote. I do not want to minimize the difficulties of building a multicultural society as Karina Piser highlighted in her talk earlier today. Sometimes French elites tend to underestimate the tensions between the majority and various minorities in the country whether it is Women, Homosexuals, Arabs, Jewish or Socio-economic minorities. Instead of admitting some level of failure in working towards a cohesive society and come up with strong, courageous and innovative solutions to remedy to this problem, many just repeat the “Vivre Ensemble” (living together) motto like a mantra, hoping things will get better while simultaneously doing little to nothing to address it. Like most men of my generation I believe that it is crucial to look at history not to repeat one’s mistakes.

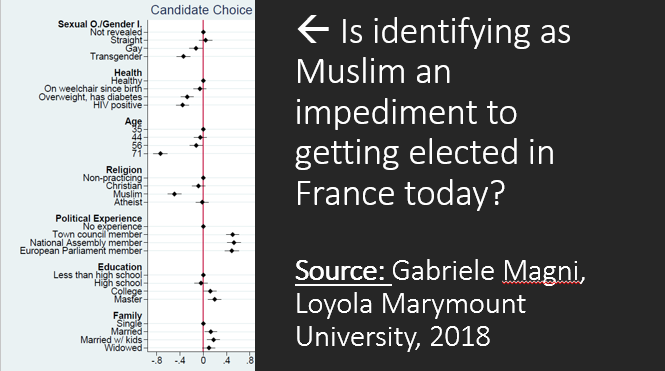

As ICWA fellow Karina Piser highlighted today at Alliance Francaise islamophobia is on the rise. A year ago, I joined in Dublin a small group of LGBTI politicians on the occasion of the launch of Andrew Reynolds’ book ”The Children of Harvey Milk” which discusses how lesbian and gay people achieved progress through getting elected to office. During the week-end, Gabriele Magni of Loyola Marymount University presented results of a 2018 study on whether voters (still) penalize lesbian, gay, transgender (LGT) candidates. He had conducted original survey experiments with nationally representative samples in France, the United States, United Kingdom and New Zealand. As I was watching the French slide, something struck me: prejudice against Muslim candidates is stronger than prejudice against gays or event trans candidate. To me, as a gay man who witnessed the amplitude of the anti-LGBT sentiment during the “manif pour tous” of 2014, it is alarming and a sign of things to come.

My point today is to highlight that the current focus on Arab immigration and its links to terrorism which Karina discussed deserves to be placed in a long history of fear linked to immigration, the erasure of a French identity and France’s past.

Back to Marseille in 1801, Theodore joined the “Egyptian refugees” in settling together in a section of the city called “Cours Gouffe” in the neighbourhood of Castellane. They might have been less than 1,000 people or 1% of the entire population of Marseille.

Here is a short description of the “Cours Gouffe” at the time [Source: adapted from Revue contemporraine, Volume 84, 1856] which highlights perfectly how the place ended up being a Levantine island in the French city: “What a curious picture that this fragment of Egypt transported as a piece of bas-relief in a French city […] The Egyptians had their Egyptian merchants, their Egyptian tailors. […] They ate as in Cairo, and slept fully clothed, as in Cairo, under mosquito nets. They did not need to buy mosquitoes; Marseilles gave them enough of them. And as soon as they felt at home, they resumed an existence of idleness characteristic of the wise East. The conversation under the plane trees, theological discussions under the vines, the horizontal life, the pipe in the mouth. The men slept during the day, the women sang towards the evening touching romances without words….”

My ancestor, Theodore joined the French army in Boulogne-sur-Mer where Napoleon was planning to invade England until the Trafalgar defeat robbed him of these dreams in 1805. He settled there and fathered a son out of wedlock in Boulogne in 1811. Like all the Egyptian refuges, Theodore received a 1 franc 50/day pension for the rest of his life. Later in Paris, Theodore worked as a sommelier for James of Rothschild. The Rothschilds covered the education of this son, Joseph, in Frankfurt. Joseph later worked for the Rotshchild family as they invested in mining in Spain in the late 1830s. Eventually, he associated himself with them in a gold refinery business and married the daughter of another of their associates. Joseph’s son, my mother’s great Grandfather, named Charles, made a fortune in a brokerage firm that bore his name. The rest is history: his descendants married into other prominent banking families: the Veyracs, Henrottes or Lenglets. My great grandmother Gabrielle Gadala born Fleury, as an example, was the daughter of a prominent Senator of Normandy. In short, the Gadalas became more French than the French all of it culminating with the birth in 1978 of very French Fabrice Houdart, yours truly.

Meanwhile, of the Egyptian families left in the “Cours Gouffe” — virtually isolated from the French population — many of them were murdered there during the White Terror of June 1815, a term used to designate a vengeance by the royalists on Imperial forces after the failed return from Elba of Napoleon “les Cents jours”. It is difficult to establish how many were killed in the massacre. Researchers have found evidence that at least twelve were killed the first day — though it is suggested that only those who belonged to more influential families were reported. Some believe as many as 150 were killed during that period. Prior to this event, a writer distinguished between the ‘‘Cophtes,’’ who carried on an honorable commerce in the town, and the ‘‘horde of miserable negros and Moors, the scum of the human species, who had lived from Bonaparte’s crumbs.’’ Perhaps more tellingly, in 1816, a return incentive program — the advance payment of one year’s pension — was put in place to incentivize the remaining families to return to Egypt. It illustrates how ttheir treatment had always be based on their usefulness to the state, which meant, above all, to Napoléon Bonaparte himself rather than refugee status: this ‘‘Egyptian” community paid a high price for its conspicuous closeness to the regime. Of those who returned to Egypt during the reign of Mehmet Ali, many were prosecuted for their collaboration with Bonaparte but others stayed and their sons — educate in the French system — contributed to developments in the Country such as the Suez Canal.

At home here in New York, I have framed a large costume engraving titled “The Mamlouk and The sailor from Alexandria” drawn by André Duterte during the Egypt campaign. I am obviously fascinated by the story of this “Egyptian ancestor”. First, my family has always considered itself as uber-Parisian and I have been told so many times in my past 19 years here in the United states that I am quintessential French: pessimistic, pale and rebellious.

So, there is something strange in acknowledging that my mother’s maiden name “Gadala” was probably given to her ancestor — who did not have a family name like most Levantines — on his arrival in Marseille by a clerk less than 200 hundred years ago. We are rather new French.

But it is also a symbol for me of the role of migrants in French history which has begun recently to be acknowledged. Any discourse on the incompatibility of immigrants of middle-eastern descent with the French culture is put to test by the contributions of the families of these egyptians that did make it out of Cours Gouffe.

Reading carefully the few papers remaining from Theodore and Joseph highlighted, it appears that this Egyptian identity was only very rarely claimed by my ancestors only in matters of pensions and to avoid service in the National Guard in 1830.

Maybe, that is a sad lesson of Theodore’s success in assimilating: integration in the French identity happened in my family through complete abandon of his identity and some erasure of their past. Until, most differences are fully erased, the French may remain suspicious of minorities. Another lesson was that his integration seems to have taken place through his engagement in the military — the great socializing force in France. The reason why France began in June a trial of compulsory civic service for teens.

Before the current focus on Arab migration, it was the Italians whom some French people stigmatized using similar terms at the end of the nineteenth century against “Italian barbarism”. I wanted to read to you an abstract from a 1903 pamphlet on the Invasion of foreigners in France which echoes a lot of the current rhetoric against Muslim families:

“The number of foreigners of all conditions who currently live with us can be evaluated without fear. 1.8 million, or nearly 5% of the total population. […]barely 60,000 live off their income or have money. The others, more than 1.7 million, take us, while escaping most of the burdens on our nationals. In some cities, in Marseilles for example, most of the big factories have eliminated from their staff to the last of our nationals […] The invasion of the Italians spreads rapidly to all Provence. In Toulon the evil rages with as much violence as in Marseilles. […] All the rejects of the five parts of the world can acquire the quality of French citizen. Better still, the legislator of 1889 imposed the quality of French on people who until then the chance of a French birth simply granted the faculty of an option. The inevitable result of this law has been that naturalizations have increased tenfold. […]. “(extract from the pamphlet (1903)).

The current focus on Arab migration also recalls a much more long-lived anti-Semitism in France through the ages. In 1939, in “La France enchainée” a newspaper close to nationalist writer Charles Maurras [1868–1952] French writer and political theorist, one could read: “the Jews conquered France, piece by piece, flap by flap; they were a thousand, they are a million … They ruined the inhabitants, the real ones. They looted everything, rotten everything, destroyed everything.”

The overestimation of the foreign population in both these extracts match Karina’s point that an Ipsos study a few years ago showed how the French hugely overestimated their country’s muslim population. French respondents guessed that their country has 31 Muslims for every 100 people but the correct number is actually 7.5.

French chauvinism and its colonial past are also factors that cannot be ignored in looking at the history of Xenophobia. France´s cultural dominance, specially over countries of Southern Europe, and their occupation of Northern African colonies are other contributing factors in the difficulties in dealing with minorities from these regions.

Yet that same history, highlights that the destiny of France and the Arab world are intrinsically linked.

The risk for the French though is to isolate islamophobia from all the other forms of prejudice against minorities that we observe globally: the Batwa in Congo, the Dalit in India, the Romas in Europe, the African-Americans in the USA or the homosexuals in all parts of the World. Whether it is skin color, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation or gender identity, hatred and oppression of one who is different or more vulnerable is unfortunately the oldest and mundane story in the world. The solution is to continue to oppose the facts to the prejudice.

I like to think that my ancestor Theodore Gadala has given much to France, descendants who died for their country, businessmen who contributed to the formation of industrial groups, a horse Hyeres III which won the grand-steeple chase from Paris not once but 3 times, an impressionist collection — some of which is now at the Met and I visit regularly with my sons — my own grandfather whose courage during the second world war I profoundly respect. And finally, your truly. This idea that whatever your politics or struggle, the color of your skin, the language that you speak, the faith you hold close, no matter whom you love, you have something unique and crucial to contribute as a Frenchman.

This is a narrative I hope we will hear more of ahead of the 2022 Presidential Election, more positive stories about the contribution of immigration to France’s history, more solution-oriented journalism like the one ICWA has supported for the past 90 years. The political exploitation of legitimate fears of terrorism and migration is a dangerous game if history taught us anything.